After the 18,000-year-old bones of diminutive people were found on the Indonesian island of Flores, the discoverers announced two years ago that these were remains of a previously unknown species of the ancestral human family. They gave it the name Homo floresiensis.

Doubts were raised almost immediately. But only now have opposing scientists from Indonesia, Australia and the United States weighed in with a comprehensive analysis based on their own first-hand examination of the bones and a single mostly complete skull.

The evidence, they reported yesterday, strongly supports their doubts. The discoverers, however, hastened to defend their initial new-species interpretation.

The critics concluded in an article in the current issue of The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that the “little people of Flores,” as they are often called, were not a newfound extinct species.

They were, instead, modern Homo sapiens who resemble pygmies now living in the region and, as suggested in particular by the skull, appear to have been afflicted with the developmental disorder microcephaly, which causes the head and brain to be much smaller than average.

The international team of paleontologists, anatomists and other researchers who conducted the study was headed by Teuku Jacob of Gadjah Mada University, who is one of Indonesia’s senior paleontologists.

In the report, Dr. Jacob and his colleagues cited 140 features of the skull that they said placed it “within modern human ranges of variation.” They also noted features of two jaws and some teeth that “either show no substantial deviation from modern Homo sapiens or share features (receding chins and rotated premolars) with Rampasasa pygmies now living near Liang Bua Cave,” where the discovery was made.

“We have eliminated the idea of a new species,” Robert B. Eckhardt, a professor of developmental genetics at Penn State who was a team member, said in a telephone interview. “After a time, this will be admitted.”

That time has not yet come.

Peter Brown, a paleontologist at the University of New England in Armidale, Australia, who was a leader of the team that discovered the “little people” bones, took sharp issue with the new report.

In an e-mail message, Dr. Brown said, “The authors provide absolutely no evidence that the unique combination of features found in Homo floresiensis are found in any modern humans.”

The features he referred to include body size, body proportions, brain size, receding chin, shape of premolar teeth and their roots, and the shape and projection of the brow ridge. But the critics asserted that many of the features in the specimen with the cranium, said to be diagnostic of a new species, are present in the Rampasasa pygmies.

Dr. Brown said the critics’ claim of “the asymmetry of the skull being the result of abnormal growth is fiction.” The skeleton was buried deep in sediment, he said, and this brought on “some slight distortion.”

In response, Dr. Eckhardt said, “Our paper accounts neatly for everything we see in the asymmetry” of the face and other parts of the skeletons.

Dr. Brown said an independent study led by Debbie Argue, an anthropologist at the Australian National University in Canberra, discounted microcephaly as an explanation. He said the report, accepted for publication in The Journal of Human Evolution, “completely supports my arguments for a new species.”

Dr. Argue’s group, which included Colin Groves, also of the Australian National University and an authority on primate taxonomy, wrote that its comparisons of the Flores specimen with modern and early humans, pygmies and microcephalic humans showed it was unlikely that the skull belonged to a microcephalic human or to any known species.

The bones at the center of the controversy were excavated from a limestone cave on Flores, an island 370 miles east of Bali, by Australian and Indonesian archaeologists.

The most complete specimen was estimated to be 18,000 years old, and other remains of as many as seven other individuals ranged from 95,000 to 13,000 years old.

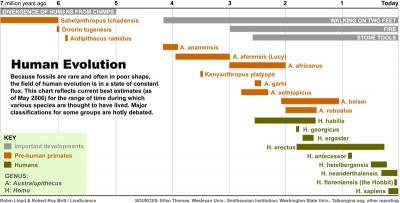

The Floresian adults stood just three and a half feet high and had brains of 380 cubic centimeters, about the size of the apelike human ancestors known as australopithecines, which lived more than three million years ago.

The find was announced in October 2004 in the journal Nature by a group headed by Michael J. Morwood, also of the University of New England. Dr. Brown was the lead author of a companion report that assigned the little people to a new human species.

In the time since, the dispute over the interpretation has often veered in nonscientific directions, sometimes trampling on national pride.

Indonesian paleontologists complained that the Australian scientists took most of the credit for the discovery and put their own stamp on the interpretations. They were also upset by what they said was the limited access they had to the specimens for their own analysis.

The discoverers countered that the Indonesian researchers had mishandled the bones. They also disparaged the quality of the critics’ research, noting that several of their rebuttals were rejected for publication in prominent journals.

On one aspect of the debate, Dr. Brown said, the discovery team has backed down. He had proposed that Homo erectus, an immediate predecessor to Homo sapiens, reached Flores 840,000 years ago and, in isolation, evolved into Homo floresiensis.

“I have moved away from the isolation and dwarfing argument,” Dr. Brown has said. “Seems most likely that they arrived small brained and small bodied.”

In their new report, the critics emphasized the facial asymmetry of the single skull specimen, known as LB1. A team member, David W. Frayer of the University of Kansas, composed split photographs of LB1’s face, combining two left or two right sides as composite faces. The dissimilarities between the original face and the two left or right composites were striking, he said.

Although most faces are not perfectly symmetrical, the scientists said, some of the differences in the two sides of the LB1 face exceeded “clinical norms” and “provided evidence for rejecting any contention that the LB1 cranium is developmentally normal.”

Maciej Henneberg, an anatomist at the University of Adelaide, Australia, and an author of the new report, said that many characteristics of the face point to a growth disorder, but that it would require much more research “to diagnose the specific syndrome present.”

Of 184 syndromes that include microcephaly, 57 cause short stature, and some also include facial asymmetry and dental anomalies. The critics said one of the next steps would be for scientists specializing in developmental disorders to join the hunt for the particular syndrome that afflicted at least one, and perhaps more of the extinct little people.

As for the species question, some scientists said it might take DNA tests to place the Floresians securely within the modern human family or somewhere on a slightly separate branch as a separate species.

Publicado en NEW YORK TIMES: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/22/science/22tiny.html?pagewanted=1&_r=2