Palm oil puts squeeze on Asia's endangered orangutan

By Gillian Murdoch Mon May 28, 12:08 AM ET

PALANGKARAYA, Central Kalimantan (Reuters) - Bound hand and foot, disheveled orangutans caught raiding Borneo's oil palm crops silently await their fate as a small crowd of plantation workers gather to watch.

ADVERTISEMENT

Lacking only hand-cuffs and finger-printing to complete the atmosphere of a criminal bust, such "ape evictions" have become part of life for Asia's endangered red apes.

Thousands have strayed into the path of international commerce as Indonesia and Malaysia, their last remaining habitats, race to convert their forests to profitable palm crops.

Branded pests for venturing out from their diminishing forest habitats into plantations where they eat young palm shoots, orangutans could be extinct in the wild in ten years time, the

United Nations said in March.

Fighting against this grim prediction is the Nyaru Menteng Borneo Orangutan Survival (BOS) centre in Central Kalimantan, which rescues orangutans and returns them to the wild at the cost of US$3,000 per ape.

"They will kill the animals if we don't go ... It's cheaper to kill the orangutan than put up a fence or snares," said Lone Droscher-Nielsen, the Danish-born founder of the centre.

While harming the apes is illegal, her centre has amassed a slew of photographs of the grisly fates of some plantation trespassers: Apes with their hands cut off and slashed to death with machetes, and others with bullets through their foreheads.

With dozens captured this year, cages are full, and finding secure land for releases is a constant challenge for the centre.

"It's not just orangutans -- bears, gibbons -- everybody is losing their home," said Droscher-Nielsen.

"If it was only the orangutan, people just say: 'Well it's only one species that's going to go extinct'. But it's not just one species. Those forests have millions of animals in them that are all going to go extinct if we continue."

SQUEEZED OUT

Indonesia and Malaysia together produce 83 percent of the world's palm oil. Made by crushing fresh fruit, the reddish-brown oil is riding high in the commodities charts, with crude prices up over 15 percent this year after rising 40 percent in 2006.

Used in cookies, toothpaste, ice cream and breads it is the world's second most popular edible oil after soy.

Demand is also soaring for palm oil-derived biofuel, despite objections from critics who slam the "green" alternative to pricey crude oil as "deforestation diesel" because of the destruction wreaked on forests to make way for palm plantations.

Of 6.5 million hectares cultivated in Malaysia and Indonesia in 2004, almost four million hectares was previously forest, environment group Friends of the Earth calculated.

For orangutan, the clearances are a matter of life and death.

"You can see how desperate the situation is," said forestry department official Sugianto, 43, as he gestured at row after row of palms in the ape's last stronghold, Central Kalimantan.

"The company knows the orangutan has a protected status ... if they have a permit to clear 60,000 hectares they clear 60,000 hectares, orangutan or not. They only care about their profit."

Caught and reported to the Borneo Orangutan Survival centre by plantations who say they are trying to be responsible stakeholders, healthy animals are re-released deep in the forest. Those too injured or too young to survive alone join 600 others at the rehabilitation centre.

Forty local Dayak women look after the current crop of 18 palm oil "orphans," whose mothers have been killed; bottle-feeding them milk, administering medicine and supervising their climbing and nest-building.

"Some people still think it is a strange job, but others think it is normal now," said 31-year old Sukawati.

After "forest school," the apes graduate to eventual release.

"They are cute and funny," said Sukawati. "They make me laugh."

BALANCING ACT

Orangutans once ranged across Southeast Asia. Now an estimated 7,300 remain on Indonesia's Sumatra island and 50,000 on Borneo island. An estimated 5,000 disappear every year.

Decades of habitat loss through rampant illegal logging, lethal annual forest fires, and poachers who earn hundreds of dollars for capturing orangutans for the illegal pet trade have all taken their toll.

But this latest threat is the worst, experts said.

"The orangutans can withstand a certain degree of logging, as most loggers don't take the orangutan food trees," said Bhayu Pamungkas of the World Wide Fund for Nature.

"But they have no chance with oil palm -& there's no chance for the orangutan if they clear-cut all the forest."

To rescue the industry's green credentials, several Indonesian and Malaysian palm oil companies have joined the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), whose voluntary criteria include a ban on clearing primary forests and areas of high conservation value, such as forests containing orangutan.

Its more than 150 members also include major European end-users like Cadbury-Schweppes, Unilever and the Body Shop, that together take 40 percent of Asian exports, and who want to buy non-destructive palm oil.

But securing private sector support is a balancing act, said Fitrian Ardiansyah, 32, an RSPO board member.

"There is some genuine intention from progressive companies to distinguish between them and the bad guys," he said.

"But if the push is too hard for them it's not going to be too difficult to switch the market to China and India, and emerging markets like the Middle East and Africa."

TREES AND PRIORITIES

Like whales, pandas, polar bears, and tigers, shaggy orange orangutan are classed "charismatic megafauna" by academics - endangered animals whose plight provokes compassion and concern.

Cute as they may be, their supporters need to keep perspective, said Derom Bangun, executive chairman of Gapki, the Indonesian Palm Oil Association, and an RSPO member.

"We should see the whole picture, not only the orangutan. They try to manipulate emotional side of orangutans so that housewives in Europe find it very pitiful," he said.

The country's clearance of almost 1.9 million hectares of forest a year between 2000 and 2005, Asia's worst deforestation rate, also needs to be seen in its economic context, Bangun said.

While the government does need to better define which forest areas are to be preserved, not all will be kept, he said.

"Other countries chopped down their forests when they were developing their countries. If they would like us to preserve more than we can, they should do something to help us."

But while plantation workers have some choice whether they want to buy into the motorbikes and mobile phones offered by palm's economic opportunities, orangutans have no such choice, those on the front-line point out.

"I'm not against palm oil," said Droscher-Nielsen. "(But) if there's not proper protection of the forest the orangutans are not going to make it."

(Additional reporting by Mita Valina Liem in Jakarta)

Visita de Wrangham y Goodall en Fundación Mona

Visita de Wrangham y Goodall en Fundación Mona

NOVES CONVOCATÒRIES ESTIU 2007

Noves Convocatòries pel Curs d’Etologia de Primats de Fundació Mona

Fundació Mona organitza des del passat mes de març de 2007 cursos d’Introducció a l’Etologia de Primats. L’objectiu fonamental d’aquests cursos és estudiar i comprendre el comportament dels primats no humans, no tan sols des d’una vessant teòrica sinó també pràctica.

La duració estimada del curs és de 15 hores (8,5 de teoria i 6,5 de pràctica) distribuïdes en dos dies (divendres i dissabte) amb un horari de 10:00 a les 18:30h. El preu de la inscripció inclou carpeta amb llibreta de camp, material en CD-ROM i certificat d’aprofitament del curs.

NOVES CONVOCATÒRIES ESTIU 2007 (Nivell Bàsic):

JULIOL: dies 20 i 21

AGOST: dies 17 i 18

SETEMBRE: dies 21 i 22

Informacions i reserves:

Miquel Llorente

e-mail: recerca@fundacionmona.org

telf: 972 477 618

**********************************************************************************

Nuevas Convocatorias para el Curso de Etología de Primates de Fundación Mona

Fundación Mona organiza desde el pasado mes de marzo de 2007 cursos de Introducción a la Etología de Primates. El objetivo fundamental de estos cursos es estudiar y comprender el comportamiento de los primates no humanos, no solo desde una vertiente teórica sino también práctica.

La duración estimada del curso es de 15 horas (8,5 de teoría y 6,5 de práctica) distribuidas en dos días (viernes y sábado) con un horario de 10:00 a les 18:30h. El precio de la inscripción incluye carpeta con libreta de campo, material en CD-ROM y certificado de aprovechamiento del curso.

NUEVAS CONVOCATORIAS VERANO 2007 (Nivel Básico):

JULIO: días 20 y 21

AGOSTO: días 17 y 18

SEPTIEMBRE: días 21 y 22

Informaciones y reservas:

Miquel Llorente

e-mail: recerca@fundacionmona.org

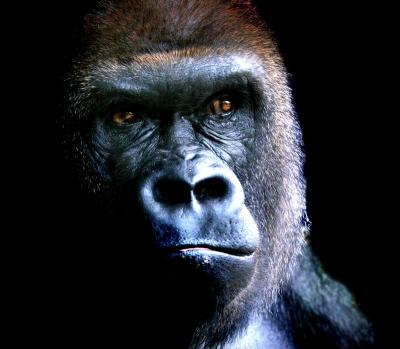

El virus ébola amenaza a la población del gorilas del Congo

El parque nacional de Ozdala, en el corazón del Congo, es una extensión de bosque tropical que cubre más de 13.200 kilómetros cuadrados y que constituye uno de los ecosistemas más misteriosos e impenetrables. Cincuenta kilómetros al suroeste del parque se localiza una región llamada Lossi. Con una extensión de unos 320 kilómetros cuadrados, el lugar acumula una concentración tan excepcional de gorilas que no se da en ningún otro lugar del mundo.

En este mundo de penumbra donde el equipo del que forma parte José Domingo Rodríguez-Teijeiro,catedrático de biología de la Universidad de Barcelona, liderado por la antropóloga Magdalena Bermejo, viene denunciando una matanza sin precedentes: más de 5.000 gorilas de llanura (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) podrían haber sucumbido ya al zarpazo del virus Ébola, el organismo más letal que se conoce, según afirman en el estudio más reciente publicado en la revista Science.

Se calcula que quedan unos 94.000 de estos animales. De acuerdo con otras estimaciones procedentes del Instituto Max Planck, el Ébola y la caza furtiva podría haber acabado ya con el 25 % de los ejemplares. "Lo que está haciendo el virus es atacar a las poblaciones grandes", explica Peter Walsh, antropólogo del Instituto Max Planck. "La mayor parte de todos los que hay en el mundo se concentran en una zona donde la gente los mata para comer, por lo que el virus y la caza pueden colocarlos en un estado de extinción ecológica". Un escenario plausible en las siguientes décadas, que presenta a los gorilas en poblaciones de unos pocos individuos, que requerirían de vigilancia y continuas intervenciones médicas para que no desaparecieran: un parque zoológico en plena selva.

Bermejo lleva observando a los gorilas desde 1994, acostumbrándolos a la presencia humana, dentro de un proyecto del programa ECOFAC (Conservación y Utilización Racional de los Ecosistemas Forestales de África Central), para incentivar el turismo ecológico en la región. Es un trabajo lento y difícil. "Hay que tener paciencia, y estar quieto, sobre todo al principio", explica Rodríguez-Teijeiro, describiendo las experiencias de su colega. "Ella ha tenido la valentía de aguantar el ataque de un espalda plateada, 200 kilos de musculatura, a medio metro, mientras el macho produce unos alaridos espantosos y muestra sus grandes incisivos. De ahí el apodo de dama de hierro con que se la conoce". Este tipo de ataques pone a prueba los nervios del observador, hasta que los animales se habitúan a su presencia.

El Ébola ha irrumpido en el proyecto de forma desastrosa. Los gorilas a los que Bermejo se ha ido aproximando con lentitud para ganarse finalmente su confianza se han desvanecido casi de la noche a la mañana. En el otoño de 2002, la epidemia se propagó hasta el límite este del santuario, y pareció detenerse en los márgenes del río. El equipo español observó entonces que varios grupos de gorilas habían sobrevivido, quizá por algún tipo de inmunidad natural, lo que alimentó las esperanzas para reemprender el programa. Fue un respiro pasajero. El virus continuó su expansión, esta vez hacia el sur, y en enero de 2004 eliminó a 91 de los 95 individuos reconocibles por el grupo de españoles. Los dos años siguientes cuentan una historia pesimista; el equipo de Bermejo cree que el virus ha limpiado de gorilas una zona de 2.700 kilómetros cuadrados.

El Ébola ha matado en África a más de 1.200 personas en un cuarto de siglo, de acuerdo con la OMS (Organización Mundial de la Salud); una cifra que, estadísticamente, es una gota en la mortalidad ocasionada por otras enfermedades tropicales, como la malaria (entre uno y cinco millones de muertes anuales), las infecciones respiratorias (más de cuatro millones), la diarrea (2,2 millones) y el sida (3 millones). Lo cierto es que, al tratarse de un "virus caliente", con una letalidad muy alta en los humanos entre el 41 % y el 100 % , la atención que despiertan los brotes de Ébola desplaza a menudo a los otros grandes matadores, menos espectaculares, aunque siniestramente más eficaces.

Las reacciones que causa el Ébola cuando irrumpe en las pobres aldeas africanas cristalizan en una palabra: terror. Al principio sólo es un dolor de cabeza que no desaparece con los analgésicos. Luego, tras una incubación extraordinariamente variable, entre 2 y 21 días, sobrevienen las fiebres y hemorragias, y la irrupción de la enfermedad es rápida y mortífera.

El patrón suele ser el mismo. Una partida de caza termina con el hallazgo de una carcasa de gorila o chimpancé infectado. Alguien lo toca, se pone enfermo y queda bajo el cuidado de la mujer en su casa. Más miembros de la familia mueren, cunde el pánico y se produce una desbandada. Si el virus ya no tiene a quien matar, el brote queda extinguido. Si alguno de los familiares llega al hospital local, contagia el virus a otras personas en la sala de espera, que retornan a sus aldeas recorriendo decenas de kilómetros a pie, extendiendo la epidemia. En las fases más virulentas de ésta, la gente simplemente abandonaba aterrorizada a sus familiares que agonizaban, o dejaban cartas en los hospitales con instrucciones de quemar sus casas y los cuerpos de sus seres queridos.

Lo que sigue trayendo de cabeza a los investigadores es el misterioso reservorio natural del virus, qué animal lo porta sin sufrir la enfermedad. La alta mortandad que ocasiona en los grandes primates los descarta de un plumazo. Algunos estudios apuntan a ciertas especies de murciélagos frugívoros y sus cuevas como los focos iniciales de transmisión, aunque no existe certeza de este hecho.

Fuente: EL PAIS. Luis Miguel Ariza

Female-led Infanticide In Wild Chimpanzees

Science Daily — Researchers observing wild chimpanzees in Uganda have discovered repeated instances of a mysterious and poorly understood behavior: female-led infanticide. The findings, reported by Simon Townsend, Katie Slocombe and colleagues of the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, and the Budongo Forest Project, Uganda, appear in the journal Current Biology.

Infanticide is known to occur in many primate species, but is generally thought of as a male trait. An exception in the realm of chimpanzee behavior was famously noted in the 1970s by Jane Goodall in her observations of Passion and Pom, a mother-daughter duo who cooperated in the killing and cannibalization of at least two infant offspring of other females. In the absence of significant additional evidence for such behavior among female chimpanzees, speculation had been that female-led infanticide represented pathological behavior, or was a means of obtaining nutritional advantage under some circumstances.

As the result of new field work involving the Sonso chimpanzee community in Budongo Forest in Uganda, the St. Andrews researchers now report instances of three female-led infanticidal attacks. Alerted to the killings by sounds of chimpanzee screams, the researchers directly observed one infanticide, and found strong circumstantial evidence for two others. Evidence suggested that in two of the cases, the killings were perpetrated by groups of resident females against "stranger" females from outside the resident group. Infants were taken from the mothers, who were injured in at least two of the attacks; in at least one case, adult males in the area exhibited displaying behavior, with one old male unsuccessfully attempting to separate the females.

The authors point out that these new observations indicate that such female-led infanticides are neither the result of isolated, pathological behaviors nor the by-product of male aggression, but instead appear to represent part of the female behavior repertoire in chimpanzees.

What drives the behavior is not yet clear, but may stem from demographic shifts that alter sex ratios and put increased pressure on females competing for foraging areas. In their report, the authors note that the Sonso community had experienced a significant population increase in the ten years prior to the infanticide observations (42 individuals in 1996 to 75 in 2006), and that there had been an influx of at least 13 females with dependent offspring since 2001. The population changes resulted in a highly skewed male:female sex ratio of 1:3, with relatively few males available to increase the home range.

According to the authors, the new findings indicate that although low-level aggression between female chimpanzees is more commonly seen, the observed instances of infanticide indicate that deadly aggression is not a gender-specific trait in this species.

Townsend et al.: "Female-led Infanticide in Wild Chimpanzees." Publishing in Current Biology, 15 May 2007, R355-356.

Note: This story has been adapted from a news release issued by Cell Press.

Chimps knocked off top of the IQ tree

The original meta-analysis of research on relative primate mental ability which is discussed in James Lee's paper was carried out by a team led by Robert Deaner, assistant psychology professor at Grand Valley State University, Allendale, Michigan. Further research on primate intelligence by Deaner and his colleagues is appearing in the journal Brain, Behavior and Evolution.

ORANG-UTANS have been named as the world’s most intelligent animal in a study that places them above chimpanzees and gorillas, the species traditionally considered closest to humans.

The study found that out of 25 species of primate, orang-utans had developed the greatest power to learn and to solve problems.

The controversial findings challenge the widespread belief that chimpanzees are the closest to humans in brainpower. They also suggest that the ancestry of orang-utans and humans may be more closely entwined than had been thought.

“It appears the orang-utan may possess a privileged status among human kindred,” said James Lee, the Harvard University psychologist behind the research. “It is even possible that an orang-utan-like forager occupied a pivotal link in the chain of descent leading to man.”

Both orang-utans and chimpanzees share about 96% of their DNA with humans, although molecular studies suggest that chimpanzees are more closely related.

The study comes at a time when orang-utans are endangered as never before. Once widespread throughout the forests of Asia, they are now confined to just two islands, Sumatra and Borneo, and are highly endangered as a result of habitat loss and poaching.

Lee’s work involved collating a series of separate studies into the intelligence of different primate species. However, his research first had to overcome a much greater hurdle: would it be possible to compare different species of primates at all?

Spider monkeys, for example, have developed brains to cope with a fast-moving life in the tree tops, while slow lorises are small and leisurely nocturnal hunters.

The conventional belief is that comparing the intelligence of different species is meaningless because separate evolution over millions of years will have given them very different brains.

Lee, a junior psychology researcher at Harvard, found that in primates, at least, different rules seem to apply — the development of one set of mental skills seems to prompt the primate brain to develop other mental abilities as well.

“A primate genus with a high rank in an experiment testing particular mental abilities appears to have high ranks in all of them,” said Lee.

He also found that the single most important factor in deciding a species’ intelligence was simply the size of its brain: “The correlation of brain size with mental ability found in humans appears to extend throughout the primate order.”

This “remarkable finding” suggests, he said, that all primate brains work in much the same way, however they have evolved, allowing comparisons between species.

Lee’s research threw up some other surprises, too. Gorillas, for example, emerged as less intelligent than spider monkeys while baboons, often considered relatively bright, were ranked 14th.

Recent field work by Carel van Schaik, a Dutch primatologist who is now at Duke University, North Carolina, appears to bear out Lee’s findings.

Studying orang-utans in Borneo, he found them capable of tasks well beyond chimpanzees’ abilities — such as using leaves to make rain hats and leakproof roofs over their sleeping nests. He also found that in some food-rich areas the creatures had developed a complex culture in which adults would teach youngsters how to make tools and find food.

He and Lee both suggest that the key factor in such developments is the orang-utans’ life-style, spent mostly in the tops of trees where there is little risk from predators. This has allowed them to establish long and settled lives similar to humans’ and also to develop culture and intelligence.

In his own research papers, Van Schaik has suggested that since the ancestors of modern orang-utans split from the human lineage about 15m years ago, the seeds of human culture must go back at least as far.

Chris Stringer, professor of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, agrees that the sociable lifestyles of primates are the driving force behind the development of intelligence. “Primates and early humans had not got the claws and teeth of predators so they had to rely on brainpower to communicate and protect themselves,” he said. “They are sociable creatures and living in small groups seems to have driven brain development.”

The idea that sociability and intelligence are linked is borne out by research into the relative brain power of diverse animal groups including cetaceans (whales and dolphins) and birds.

Dr Vincent Janik, of the sea mammal research unit at St Andrews University, said that some dolphin species had developed the ability to communicate far beyond that of great apes. “Dolphins have some abilities that great apes don’t have, such as copying new sounds. No primate apart from humans can do that,” he said.

Additional reporting: Max Colchester

Non-human primates in order of intelligence

1 Orang-utan

2 Chimpanzee

3 Spider monkey

4 Langur

5 Macaque

6 Mandrill

7 Guenon

8 Mangabey

9 Capuchin

10 Gibbon

11 Baboon

12 Woolly monkey

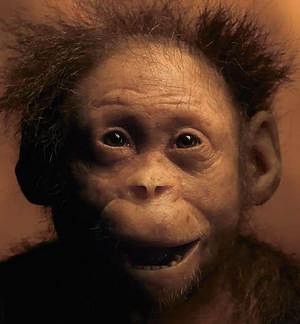

El bressol de Selam

Fuente: El Periódico de Catalunya

BARCELONA

Alemseged, investigador de l'Institut Max Planck d'Alemanya, va estar la setmana passada a Barcelona, convidat per l'Obra Social La Caixa, per pronunciar una conferència sobre el descobriment que l'ha fet famós. Selam, presentada en societat l'any passat, és un fòssil d'Australopithecus afarensis d'un valor excepcional per qualsevol dels següents tres motius: la seva gran antiguitat, uns 3,3 milions d'anys; la seva excel.lent conservació, amb l'esquelet complet al 60% i alguns ossos extraordinaris per a èpoques tan remotes, com el hioide i l'omòplat, i finalment el seu desenvolupament anatòmic, ja que és un individu infantil d'uns tres anys, escassíssims en el registre fòssil mundial.

"¿Va ser sort? Jo crec que no. La troballa va ser possible gràcies a un treball sistemàtic que vaig iniciar el 1999 --explica Alemseged en una entrevista amb aquest diari--. Quan vaig arribar a Dikika, volia explorar sediments més antics que els trobats a Hadar, on va aparèixer Lucy (el famós A. afarensis que va ser descobert el 1974 en una zona pròxima), i em vaig plantejar una àrea de 500 quilòmetres quadrats. El 10 de desembre del 2000, quan vaig trobar els ossos, estava analitzant una de les zones previstes".

La desèrtica Dikika era fa 3,3 milions d'anys una regió molt biodiversa, amb sabanes i boscos on vivien hipopòtams, lleons, antílops, elefants i, per descomptat, australopitecs, unes curioses criatures d'aspecte simiesc que caminaven bípedes. "Avui és un desafiament viure allà --reitera el jove investigador--, però en temps de Selam i Lucy era una regió molt favorable perquè hi poguessin viure els nostres avantpassats".

Potser hi va haver altres enclavaments pròxims amb presència d'australopitecs, però a Dikika va ocórrer un succés miraculós: possiblement, la nena estava bevent o jugant arran d'un riu quan va ser sorpresa per una riuada que va descarregar en un llac. El seu cos va quedar cobert per sediments d'argila que es van soldar i van contribuir a la conservació. "La majoria dels paleontòlegs han de recompondre ossos trencats i buscar restes disperses de l'esquelet, mentre que jo vaig tenir el repte contrari: tenia els ossos units en una gran roca sedimentària i havia de separar-los amb molt de compte perquè no es fracturessin". Com que no es pot utilitzar àcid perquè les restes es fan malbé, el treball dels investigadors va durar cinc anys.

A la regió d'Afar, el moviment de les plaques terrestres ha anat traient a la llum fòssils que van quedar enterrats fa milions d'anys. Alguns afloren a la superfície. La riquesa paleontològica de la regió no té cap parangó al món per a èpoques tan remotes, ja que també hi han aparegut ossos d'Australopithecus anamensis (4,1 milions d'anys) i d'Ardipithecus ramidus (4,4 milions), però no és fàcil que Afar se'n beneficiï, assumeix l'investigador. "Els turistes que busquen llocs com Hadar o Dikika són molt escassos. El turisme vol veure obeliscos i esglésies".

Jaciment de primer ordre

Les restes es conservaran al museu nacional d'Addis Abeba, però Alemseged aspira a crear un centre d'interpretació situat relativament a prop de Dikika. "¡Com hem de tenir un museu al costat si no hi ha ni clínica ni escola! Però s'ha de vigilar, perquè els fòssils estan a l'aire lliure". A Dikika, convertit en un jaciment de primer ordre, ja hi treballen 35 persones amb patrocinis diversos.

L'investigador està orgullós de servir d'exemple per a una nova generació d'etíops: "La paleontologia va començar aquí en temps de Haile Selassie, es va paralitzar amb el règim comunista i ara es torna a despertar, però al meu país no hi ha ni la més mínima tradició investigadora. Tot i que afortunadament no sóc l'únic, sí que som pocs". Fins ara, tots els paleontòlegs a l'Àfrica eren estrangers. Alemseged és jove, però ja té deixebles.

Like humans, apes can communicate manually

Before there was speech, there was the gesture — a hand outstretched to beg for food, or a "come hither" sweep of a beckoning forearm. Monkeys may see. But when it comes to gestures, only apes — and humans — do. That discovery, by researchers at Emory University's Yerkes National Primate Research Center, offers new fuel for the theory that the evolution of human language began, not with words, but with a wave of the hand or a flick of the wrist. "Our research suggests that just as human babies can learn certain gestures before they speak, our ancestors may have been gesturing to each other before they talked," says Yerkes researcher Frans B.M. de Waal. Language, the fundamental mechanism by which humans share information, is thought to have emerged about 100,000 years ago. But the study by de Waal and Yerkes co-researcher Amy Pollick, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, suggests that nonvocal communication — perhaps hand gestures exchanged by prehistoric hunters — may have appeared much earlier. Although monkeys and other primates have a wide range of facial expression and body postures, de Waal says only the apes — chimps, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans — use controlled manual gestures. Those gestures, like spoken language, are flexible enough to have different meanings in different contexts and vary from group to group. "The difference in control is dramatically illustrated by past failure to teach chimpanzees to speak, even though they have no trouble learning the gestures of American sign language." From their daily observations of two groups of chimps at the Yerkes center in Atlanta and two groups of bonobos at the San Diego Zoo, the researchers documented 31 distinct manual gestures — including pointing, waving, beckoning, and rapping knuckles, whose meanings varied enormously from group to group. "A chimpanzee stretching out an open hand toward a possessor of food, for instance, signals a desire for food, but stretching out an open hand toward a third party during a fight signals a need for support," explains de Waal. "You can see similar contextual differences in someone begging on the street." The British primatologist Jane Goodall first noted gesturing among chimpanzees in the wild in the 1960s. But de Waal, the author of "Our Inner Ape," "Chimpanzee Politics," "Peacemaking Among Primates," and other books, says the ability has since been documented in all apes, which are humans' closest relatives on the evolutionary tree.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Published on: 05/01/07

Chimpanzees Are Actually Three Distinct Groups, Gene Study Shows

Science Daily — The largest study to date of genetic variation among chimpanzees has found that the traditional, geography-based sorting of chimps into three populations--western, central and eastern--is underpinned by significant genetic differences, two to three times greater than the variation between the most different human populations.

In the April 2007 issue of the journal PLOS Genetics, researchers from the University of Chicago, Harvard, the Broad Institute and Arizona State show that there has been very little detectable admixture between the different populations and that chimps from the central and eastern populations are more closely related to each other than they are to the western "subspecies."

They also devised a simplified set of about 30 DNA markers that zookeepers or primatologists could use to determine the origins of a chimpanzee with uncertain heritage.

"Finding such a marked difference between the three groups has important implications for conservation," said Molly Przeworski, PhD, assistant professor of human genetics at the University of Chicago and a senior author of the study. "It means we have to protect three separate habitats, all threatened, instead of just one."

To unravel the evolutionary history to chimpanzees, the research team collected DNA from 78 common chimpanzees and six bonobos, a separate species of chimpanzee, and examined 310 DNA markers from each.

They found four "discontinuous populations," three of common chimps plus the bonobos. Hybrids, those with at least five percent of their DNA from more than one common chimpanzee population were rare, with most of the hybrid chimps born in captivity.

"We saw little evidence of migration between groups in the wild," said Celine Becquet, first author of the paper and a graduate student in Przeworski's laboratory. "Part of that could stem from the gaps in our samples, but we think most of this separation is genuine, a long-term consequence of geographic isolation."

The original boundaries between groups may have been the emergence and growth of rivers, such as the Congo River, which is thought to be about 1.5 million years old. "Chimps don't swim," Becquet said. "For them, water provides a very effective border." The ongoing loss of habitat has increased the physical separation between the three groups.

The extent of accumulated genetic difference enabled the researchers to speculate about when the different populations separated. They estimate that bonobos, which live south of the Congo River, split off from the ancestors of modern chimpanzees about 800,000 years ago. Western chimps appear to have separated from central and eastern chimpanzees about 500,000 years ago and central and eastern chimps divided about 250,000 years ago.

"Even though the chimp genome has been sequenced, it's amazing how little we know about their evolution and the level of variation within chimpanzees," said Przeworski. "These are our nearest relatives, closer to humans than they are to gorillas, yet we know so little about them, and even less about gorillas and orangutans."

The chimpanzee genome differs from the bonobo genome by about 0.3 percent, which is one-fourth the distance between humans and chimps. Yet chimps and bonobos have radically different social systems, cultures, diets and mating systems.

On the other hand, in this study, looking at three "subspecies" of common chimpanzees, "we found significant genetic variation," said Przeworski, "but there's very little detectable difference between the populations in terms of appearance or behavior."

The National Institutes of Health, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Burroughs Wellcome Fund and the National Science Foundation funded this study. Additional authors include Nick Patterson and David Reich of the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT and Anne Stone of Arizona State.

Note: This story has been adapted from a news release issued by University of Chicago Medical Center.

Alumnes de Psicologia de la UdG treballen amb simis a Fundació Mona

Des del passat mes de desembre de 2006, dues alumnes de l´últim curs de la Llicenciatura de Psicologia de la Universitat de Girona, Pilar Berengué i Anna Portell, col·laboren en la recollida de dades pel projecte Interaccions socials entre tres grups de ximpanzés en el CRP de la Fundació Mona.

L´objectiu d´aquest treball de camp és estudiar els processos de ressocialització dels ximpanzés allotjats a Mona, que sovint han estat víctimes de maltractaments. El projecte es va iniciar en el marc del Màster d´Etologia dels Primats de la Universitat de Barcelona, amb qui Fundació Mona col·labora des de 2005.

Gràcies al conveni de pràcticum establert amb la Facultat d´Educació i Psicologia de la Universitat de Girona, l´estudi continuarà aprofundint sobre el comportament social dels grups de ximpanzés, la seva evolució i adaptació

Fuente: Diari de Girona, 4-04-2007

Investigadors de la Universitat Lusófona fan una estada a Fundació Mona

“Investigadors de la Universitat Lusófona fan una estada a Fundació Mona”

Dos investigadors de la Universitat Lusófona de Lisboa (Portugal) realitzen una estada a Fundació Mona des del present mes de gener fins al proper mes de juny de 2007. Coordinats per la Dra. Augusta Gaspar, professora d’Etologia d’aquesta mateixa universitat, portaran a terme dos interessants treballs de recerca en col·laboració amb Fundació Mona.

Per una banda, Gonçalo Jesús farà un estudi sobre les “expressions facials de sorpresa en ximpanzés”. D’altra banda, Sílvia Rocha el realitzarà sobre “l’enriquiment ambiental com a eina d’atracció social, socialització i reducció de l’estrès en ximpanzés”.

D’aquesta manera, Fundació Mona obre una nova via de col·laboració amb prestigioses universitats i grups de recerca europeus, amb l’objectiu de convertir a Mona en un referent de la primatologia a nivell internacional.

Per a més informació adreçar-se a: recerca@fundacionmona.org

“Investigadores de la Universidade Lusófona realizan una estancia en Fundación Mona”

Dos investigadores de la Universidade Lusófona de Lisboa (Portugal) realizan una estancia en Fundación Mona desde el presente mes de enero hasta el próximo mes de junio de 2007. Coordinados por la Dra. Augusta Gaspar, profesora de etología de esta universidad realizarán dos interesantes proyectos de investigación en colaboración con Fundación Mona.

Por un lado, Gonçalo Jesús llevará a cabo un estudio sobre las “expresiones faciales de sorpresa en chimpancés”. Por otro lado, Sílvia Rocha llevará a cabo un estudio sobre el “enriquecimiento ambiental como herramienta de atracción social, socialización y reducción del estrés en chimpancés”.

De esta manera, Fundación Mona abre una nueva vía de colaboración con prestigiosas universidades y grupos de investigación europeos, con el objetivo de convertir a Mona en un referente de la primatología a nivel internacional.

Para más información dirigirse a: recerca@fundacionmona.org

"Researchers of the University Lusófona make a stay in Mona Foundation"

Two researchers of the University Lusófona of Lisbon (Portugal) carry out a stay in Mona Foundation since the present month of January until the next month of June of 2007. Coordinated by the Dr. Augusta Gaspar, professor of Ethology of this same university, they’ll do two interesting research projects in collaboration with Mona Foundation.

On the one hand, Gonçalo Jesús will make a study about the "facial expressions of surprise in chimpanzees". On the other hand, Sílvia Rocha will carry it out about "the environmental enrichment as a tool of social attraction, socialization and stress reduction in chimpanzees".

In this way, Mona Foundation opens a new way of collaboration with prestigious universities and European groups of research, with the goal to convert Mona in a primatology referent at international level.

For more information: recerca@fundacionmona.org

FUNDACIÓ MONA A CUBA, CONVIDADA A PARTICIPAR EN UN CONGRÉS SOBRE ANTROPOLOGIA

FUNDACIÓ MONA A CUBA, CONVIDADA A PARTICIPAR EN UN CONGRÉS SOBRE ANTROPOLOGIA

La humanització i deshumanització de ximpanzés que viuen a Fundació Mona ha estat objecte d’interès a Anthropos 2007 (Congrés Iberoamericà d’Antropologia), que amb el lema l’Antropologia davant els reptes del segle XXI es va celebrar durant el 5 i 9 de març a la localitat de l’Havana, Cuba. La Dra. Marina Mosquera, professora i investigadora de l’Àrea de Prehistòria de la Universitat Rovira i Virgili de Tarragona, va ser l’encarregada de presentar en una conferència plenària les diferents investigacions que es desenvolupen a Fundació Mona en col·laboració amb l’IPHES (Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social), dirigit per Eudald Carbonell.

La conferència impartida, amb el títol “Humanització i deshumanització de ximpanzés en semillibertat: lateralitat manual com a element de rastreig en l’evolució humana” i firmada conjuntament amb la Dra. Mosquera per Miquel Llorente i David Riba, investigadors de l’IPHES i Fundació Mona, va repassar la història i els orígens de Mona i els seus principals projectes de recerca. Finalment va concloure centrant-se en els primers resultats obtinguts en el nostre principal projecte de recerca sobre la lateralització manual dels ximpanzés de Mona, el projecte PANLAT.

De nou, Mona està present en els principals àmbits i cercles científics com a centre de primatologia de referència dins l’àmbit internacional.

Per a més informació: Miquel Llorente, recerca@fundacionmona.org

FUNDACIÓN MONA EN CUBA, INVITADA A PARTICIPAR EN UN CONGRESO SOBRE ANTROPOLOGÍA

La humanización y deshumanización de chimpancés que viven a Fundación Mona ha sido objeto de interés en Anthropos 2007 (Congreso Iberoamericano de Antropología), que con el lema la Antropología ante los retos del siglo XXI se celebró durante el 5 y 9 de marzo en la localidad de la Habana, Cuba. La Dra. Marina Mosquera, profesora e investigadora del Área de Prehistoria de la Universidad Rovira y Virgili de Tarragona, fue la encargada de presentar en una conferencia plenaria las diferentes investigaciones que se desarrollan en Fundación Mona en colaboración con el IPHES (Instituto Catalán de Paleoecología Humana y Evolución Social), dirigido por Eudald Carbonell.

La conferencia impartida, con el título "Humanización y deshumanización de chimpancés en semilibertad: lateralidad manual como elemento de rastreo en la evolución humana" y firmada conjuntamente con la Dra. Mosquera por Miquel Llorente y David Riba, investigadores del IPHES y Fundación Mona, repasó la historia y los orígenes de Mona y sus principales proyectos de investigación. Finalmente concluyó centrándose en los primeros resultados obtenidos en nuestro principal proyecto de investigación sobre la lateralización manual de los chimpancés de Mona, el proyecto PANLAT.

De nuevo, Mona está presente en los principales ámbitos y círculos científicos como centro de primatologia de referencia dentro del ámbito internacional.

Para más información: Miquel Llorente, recerca@fundacionmona.org

MONA FOUNDATION INVITED TO CUBA TO PARTICIPATE IN A CONGRESS ABOUT ANTHROPOLOGY

The humanization and dehumanization of the chimpanzees that live Mona Foundation has been object of interest in Anthropos 2007 (Iberoamerican Congress of Anthropology), with the lemma of Anthropology facing the challenges of the 21st century celebrated during the 5th and 9th of March in La Havana, Cuba. Dr. Marina Mosquera, teacher and researcher of Prehistory Area of Universitat Rovira i Virgili from Tarragona, presented in a full lecture Mona Foundation and the different researchs that develops in collaboration with the IPHES (Catalan Institute of Human Paleo-Ecology and Social Evolution), directed by Eudald Carbonell.

The lecture, with the title "Humanization and dehumanization of chimpanzees in semi-free conditions: manual laterality as an element of tracking in the human evolution" was signed together with Dr. Mosquera by Miquel Llorente and David Riba, researchers of the IPHES and Mona Foundation. The lecture revised the history and the origins of Mona and its main research projects. Finally, it focussed on the first results obtained from the chimpanzees of Mona in our main project of research about the lateralization, in the framework of PANLAT project.

Again, Mona is in the main areas and scientific circles as an international center of reference in primatology.

For further information: Miquel Llorente, recerca@fundacionmona.org

Els orangutans podrien desaparèixer d'aquí a uns 10 anys

Una parella d'orangutans i la seva cria, en una reserva d'animals a Indonèsia. Foto: ARXIU / AP

Una parella d'orangutans i la seva cria, en una reserva d'animals a Indonèsia. Foto: ARXIU / AP JAKARTA

Les illes de Borneo i Sumatra són l'últim lloc del món on queden orangutans en llibertat, però aquesta espècie es podria extingir d'aquí a 10 anys si continua el ritme actual desaparició, segons els experts.

Les últimes dades aportades pels centres de conservació d'orangutans a Indonèsia indiquen que només queden al país uns 5.000 exemplars de l'espècie de Sumatra i entre 15.000 o 20.000 de la de Borneo. Aquesta xifra és molt inferior als 60.000 que recollia l'últim cens oficial, elaborat a finals dels anys 90.

"Es considera que l'orangutan estarà mort genèticament d'aquí a entre cinc i deu anys. Això significa que no quedaran suficients animals perquè l'espècie sigui viable genèticament", ha explicat Karmele Pla, veterinària espanyola que treballa a Indonèsia en la conservació d'aquests i d'altres primats.

Transcorregut aquest període encara quedaran alguns orangutans però seran "poblacions inviables", es produirà endogàmia, augmentarà la mortaldat i els animals patiran noves malalties que els mataran o que impediran la seva vida en llibertat, ha afegit.

Desforestació per produir biocombustible

Per Pla, la principal amenaça que pateixen avui dia els orangutans és la desforestació (legal i il·legal) per deixar lloc a plantacions destinades a produir oli de palma, que després és utilitzat per fabricar biocombustible, amb una demanda que no fa més que créixer en el primer món.

Cada any cremen a Indonèsia centenars d'hectàrees de bosc tropical per deixar pas a les plantacions de palmeres, cosa que segons Pla està tenint un "efecte devastador" en les poblacions d'orangutans i altres animals, a més de fer el biocombustible més perjudicial per al medi ambient que la gasolina.

Se presentan en Tarragona los proyectos de investigación de Fundación Mona dentro de una conferencia sobre la Evolución de la Cognición Humana

El pasado día 28 de febrero y dentro de una conferencia con el título "Cerebro, comportamiento complejo, pensamiento simbólico y tecnología", Marina Mosquera profesora titular del Área de Prehistoria de la Universidad Rovira i Virgili e investigadora del IPHES (Instituto Catalán de Paleoecología Humana y Evolución Social) presentó parte de los proyectos de investigación que Fundación Mona viene llevando a cabo en colaboración con estas instituciones desde el año 2002.

Uno de los principales objetivos de las investigaciones que llevan a cabo en Mona es poder aportar más conocimientos sobre los orígenes evolutivos de nuestro comportamiento. Esto incluye un amplio abanico de temáticas de estudio como son la lateralización manual y cerebral, la cognición espacial, el aprendizaje social, el comportamiento social o el uso y fabricación de herramientas por parte de los chimpancés. De esta manera, hoy día proyectos como el PANLAT (estudio de la lateralización manual y cerebral en chimpancés) nos pueden aportar una información muy valiosa sobre cuáles son las raíces evolutivas de nuestro funcionamiento cerebral, y dar pistas sobre los orígenes del lenguaje humano y el comportamiento tecnológico.

De esta manera, nuestras investigaciones, todas ellas de carácter no invasivo y respetando y fomentando el bienestar de los animales, comienzan a ser un punto de referencia dentro del ámbito de la primatologia nacional e internacional.

Para más información:

Miquel Llorente

Crédito foto: Gerard Campeny (IPHES)

Armed and dangerous

The discovery of a chimpanzee making and using a spear in Senegal is not only a surprising revelation about our nearest evolutionary relative, say Mairi MacLeod and Ian Sample - it could also provide invaluable insights into how man developed technology

Friday February 23, 2007

The Guardian

In the dry heat of the west African savanna, a chimp called Tumbo hauled herself up into a wizened tree. She had spotted something: an interesting-looking hole at a fork in the trunk. Watching her, researcher Paco Bertolani suspected that she was looking for insect larvae to eat; the chimpanzees had done this before. Tumbo grabbed a thin branch, snapped it free and purposefully honed one end, using her teeth to make a point. Then, she moved closer to the hole, grasped the primitive spear, and rammed it inside with as much might as she could muster. Afterwards, she pulled it out and sniffed and licked the end. Tumbo repeated the violent stabs again and again until, apparently satisfied, she moved across to a withered branch adjoining the trunk and leapt up and down to break it free. From within the now exposed hole, she retrieved an unmoving bushbaby, evidently dead as a result of the onslaught. She sat down and calmly dismembered the animal, chewing on the meat with relish and accompanying her meal with odd handfuls of fresh leaves.

Tumbo is the first chimpanzee to be seen making and using a tool to hunt for meat. Details of her spearing her prey are revealed for the first time today in the journal Current Biology. Such behaviour has never been seen before, and it represents an important leap forward in our understanding of just how sophisticated chimpanzees - humankind's closest relatives - really are.

There was a time when scientists believed that one of the major differences between us (humans) and them (animals) was tool use. But those days are long gone. Last year, chimps in the Congo were captured by hidden video cameras using stick tools to dig and dangle for termites. Earlier this month, a crop of ancient stone tools dating back 4,300 years were unearthed and identified as having been used by chimps, fuelling a debate about a chimpanzee Stone Age and the chance that both chimps and early humans inherited tool use from a common ancestor. Now there's Tumbo using a spear.

We have certainly come a long way since a young Jane Goodall began her inspirational research into chimpanzee behaviour at Gombe in Tanzania in the 1960s, back in the days when chimps were seen as innocent, peace-loving creatures (since then, they have been observed hunting down monkeys in coordinated groups, not to mention murdering each other). Increasingly, chimp behaviour is being found to be so human-like that it is giving scientists invaluable insights into the evolution of early humans.

"Technology is one of the most important aspects of the human condition. It's the reason we've conquered the planet, but it had to come from somewhere," says William McGrew, a primatologist and expert on the evolution of material culture at Cambridge University. "Short of inventing a time machine, the next best thing is to look at our nearest living relations and their technology." According to McGrew, evidence from the archeological record suggests that our hominid ancestors started using tools in hunting around 400,000 years ago in Europe. "And what do you think [they used]?" he asks. "Sharpened wooden sticks. It is essentially the same weapon that's being used by these apes, except it's bigger."

But why has spear-making by chimpanzees never been seen elsewhere, despite decades of research? The reason could be that chimp behaviour in this particular habitat - the hot, dry savanna of Fongoli in Senegal - has not been studied in detail before. Chimps adopt different strategies in different environments: complex cultural differences have emerged between populations. And the Fongoli chimps do seem to be quite an unusual population. As well as using spears, they have taken up residence in a number of caves, worn from rock by millennia of flowing water. It seems they like to use them for picnics and siestas, or to shelter from the heat during the day.

Bertolani, of Cambridge University, who is collecting data for his PhD, once spent the day with Fongoli chimps in one of their more open caves and witnessed events not out of place in a soap opera. He says some rested and groomed, others quarrelled, while males showed off, running in and out of the cave for the benefit of a female. Others did their best to ignore the spectacle and carried on sleeping in the dark recesses. Researchers have also witnessed the chimp equivalent of a pool party - with no little astonishment, because chimps usually have a strong aversion to water. "Chimps are reckoned to be hydrophobic, because they sink like stones," says McGrew. "Then along come the Fongoli chimps, who, when the rains come in May and fill up the depressions in the plateaus, jump in and sit there up to their chests, all crammed in together."

"They run through and splash each other and display," says Jill Pruetz, director of the Fongoli project at Iowa State University.

One of the most intriguing things about the Fongoli spear use is that it is females who do the hunting. Monkey hunts by chimps are well documented, but they are dominated by the big males. Although females occasionally take part in hunts, it's normally a back-seat role. Charging through the trees is dangerous, especially with a small infant, and even if a female catches the quarry, there's a good chance she will have to surrender it to a larger male.

Pruetz says females and youngsters are forced to innovate to get protein for their diets; her point is that it is females who are driving the adoption of new technology. "The females and maybe the young males too are basically having to solve problems in a creative way because of competition with adult males," she says. "That may be by technology, and not by brute strength or force."

"Basically, you can spot that tree hole and you can creep up and take a good look," says McGrew. "You can do that even if you're encumbered with an infant, and because it's a solitary activity, you don't have to coordinate with others."

The researchers say spear use in Fongoli is performed almost exclusively by females and youngsters. In spite of the fact that the researchers were concentrating on male behaviour during their study, they saw only one attempt at spear-making by an adult male out of a total of 22 episodes.

"[This] strengthens the case that in all likelihood the origins of technology [in humans] were with females," says McGrew.

The chimpanzees at Fongoli have been habituated to humans for less than two years. In that short time researchers have discovered a wealth of new chimpanzee behaviour. What else are these apes going to surprise us with? Pruetz says she is learning to expect the unexpected and is hoping that it will be possible to keep the research going at Fongoli far into the future. So we know now that chimps are skilled and cooperative hunters. We know they are capable of terrible violence, but also empathy and, according to some observers, even primitive morality. We see the roots of human behaviour in wild chimpanzees today: they are on a behavioural continuum with us. But how far, if anywhere, will their technology go? Humans achieved great leaps in technology only after millions of years of environmental pressure gave rise to more complex brains.

"Chimps do a pretty good job of tackling their problems without developing technology. What's instructive is when they need it," says McGrew. Chimps have the advantage of big, strong jaws and teeth, he says, so they can accomplish many of their jobs without tools. But, he says, "even after human technology took off, it took millions of years to get notable changes, so for us primatologists to be lucky enough to see anything in a couple of decades is highly unlikely. Every one of us would love to be on the scene when there's an important advance in chimp technology. It hasn't happened yet, but we live in hope."

Hunting chimps may change view of human evolution

By Maggie Fox, Health and Science EditorThu Feb 22, 12:50 PM ET

Chimpanzees have been seen using spears to hunt bush babies, U.S. researchers said on Thursday in a study that demonstrates a whole new level of tool use and planning by our closest living relatives.

Perhaps even more intriguing, it was only the females who fashioned and used the wooden spears, Jill Pruetz and Paco Bertolani of Iowa State University reported.

Bertolani saw an adolescent female chimp use a spear to stab a bush baby as it slept in a tree hollow, pull it out and eat it.

Pruetz and Bertolani, now at Cambridge University in Britain, had been watching the Fongoli community of savanna-dwelling chimpanzees in southeastern Senegal.

The chimps apparently had to invent new ways to gather food because they live in an unusual area for their species, the researchers report in the journal Current Biology.

"This is just an innovative way of having to make up for a pretty harsh environment," Pruetz said in a telephone interview. The chimps must come down from trees to gather food and rest in dry caves during the hot season.

"It is similar to what we say about early hominids that lived maybe 6 million years ago and were basically the precursors to humans."

Chimpanzees are genetically the closest living relatives to human beings, sharing more than 98 percent of our DNA. Scientists believe the precursors to chimps and humans split off from a common ancestor about 7 million years ago.

Chimps are known to use tools to crack open nuts and fish for termites. Some birds use tools, as do other animals such as gorillas, orangutans and even naked mole rats.

But the sophisticated use of a tool to hunt with had never been seen.

Pruetz thought it was a fluke when Bertolani saw the adolescent female hunt and kill the bush baby, a tiny nocturnal primate.

But then she saw almost the same thing. "I saw the behavior over the course of 19 days almost daily," she said.

PLANNING AND FORESIGHT

The chimps choose a branch, strip it of leaves and twigs, trim it down to a stable size and then chew the ends to a point. Then they use it to stab into holes where bush babies might be sleeping.

It is not a highly successful method of hunting. They only ever saw one chimpanzee succeed in getting a bush baby once. The apes mostly eat fruit, bark and legumes.

Part of the problem is this group of chimps is shy of humans, and the females, who seem to do most of this type of hunting, are especially wary. "I am willing to bet the females do it even more than we have seen," she said.

Pruetz noted that male chimps never used the spears. She believes the males use their greater strength and size to grab food and kill prey more easily, so the females must come up with other methods.

"That to me was just as intriguing if not even more so," Pruetz said.

The spear-hunting occurred when the group was foraging together, again unchimplike behavior that might produce more competition between males and females, she said.

Maybe females invented weapons for hunting, Pruetz said.

"The observation that individuals hunting with tools include females and immature chimpanzees suggests that we should rethink traditional explanations for the evolution of such behavior in our own lineage," she concluded in her paper.

"The multiple steps taken by Fongoli chimpanzees in making tools to dispatch mammalian prey involve the kind of foresight and intellectual complexity that most likely typified early human relatives."

Cursos Etología de Primates en Fundación MONA

Fundación Mona organiza, a partir del próximo mes de marzo de 2007, cursos de Etología de Primates. El objetivo fundamental de estos cursos es estudiar y comprender el comportamiento de los primates no humanos, no tan sólo desde una vertiente teórica sino también práctica. Por tanto, dedicaremos un 43% del tiempo a la práctica de observación etológica de los animales alojados en el Centro de Recuperación de Primates de Fundación Mona, y un 57% a teoría.

La duración estimada del curso es de 15 horas (8,5 de teoría y 6,5 de práctica) distribuidas en dos días (viernes y sábado), y se llevará a cabo el tercer fin de semana de cada mes. El horario de desarrollo del curso es de 10:oo a 18.30 horas.

El precio de la inscripción incluye carpeta con libreta de campo, material en CD-ROM y certificado de aprovechamiento del curso.

Próximas convocatorias primer semestre de 2007 (Nivel Básico):

Días 16 y 17 de marzo

Días 20 y 21 de abril

Días 18 y 19 de mayo

Días 15 y 16 de junio

Para más información en relación a los cursos:

Persona de contacto: Miquel Llorente

tel: 972 477 618

e-mail: recerca@fundacionmona.org

Acceso libre a la investigación financiada con fondos públicos

Estimados colegas

En estos tiempos que corren (literal y figuradamente) la evolución de las

pautas de diseminación de los resultados de la investigación parece

encaminarse a un sistema donde sólo unas pocas grandes editoriales dominan

el negocio. Ello lleva a que los resultados de una investigación financiada

con dinero público se publiquen en revistas de alto prestigio, pero que son

inaccesibles para la gran mayoría, por los precios prohibitivos que se cobra

por el acceso.

Existe en estos momentos una iniciativa europea que intenta cambiar esa

política, al menos en la EU. Os invito a leer, y si lo consideráis oportuno,

firmar la declaración disponible en :http://www.ec-petition.eu/

Saludos

Adolfo Cordero

Adolfo Cordero Rivera

Catedrático de Ecoloxía / Professor of Ecology

Universidade de Vigo

EUET Forestal, Campus Universitario,

36005 Pontevedra, Galiza, España / Spain

Grupo de Ecoloxía Evolutiva

adolfo.cordero@uvigo.es

http://webs.uvigo.es/adolfo.cordero/index.htm

tel: +34 986 801926

fax: +34 986 801907

móbil: +34 6473 43183

(43183 dende extensións da Universidade)