Efectes de la utilització de primats en l'espectacle i la publicitat

La utilització de primats en publicitat i altres medis similars té un impacte negatiu sobre els esforços de conservació d’aquesta espècie que es troba en un greu perill d’extinció (Butynski y Members of the Primates Specialist Group, 2000), fomentant el tràfil il·legal d’aquestes espècies i contribuint a empitjorar lamentablement la situació en la que es troben els primats en els seus llocs d’origen (Feliu y Llorente, 2005).

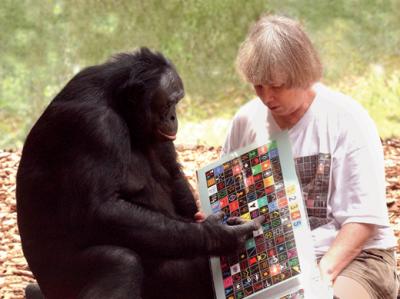

Els primats són éssers socials per naturalesa. Avui dia, existeix el consens general que els primats necessiten de la companyia social d’altres individus de la seva espècie (Reinhardt y Reinhardt, 2000). Des del punt de vista del benestar animal, és molt important mantenir a aquests animals socials en unes condicions que els hi permeti desenvolupar un gran repertori de conductes pròpies de la seva espècie. D’aquesta manera, el benestar animal és directament proporcional a la integració que té en un grup (Feliu y Llorente, 2005). Fins ara, la resocialització és l’únic camí per tal de proporcionar a qualsevol ximpanzé captiu l’oportunitat de convertir-se en un individu normal i social (Fritz, 1986), però resulta molt complicada, llarga, costosa i moltes vegades impossible (Brent, Kessel, y Barrera, 1997). Un cop retirats del món de l’espectacle i la publicitat quan arriben a l’etapa adulta, aquests animals acostumen a trobar-se en un estat físic i condicions psicològiques molt pobres amb la conseqüent necessitat de rehabilitació i resocialització (Nash, Fritz, Alford, y Brent, 1999).

Els individus que han viscut en una situació de deprivació psicosocial mostren estar infraequipats física i psicològicament per a enfrontar-se o superar situacions estressants (Sackett, Novak, y Kroeker, 1999; Turner, Davenport, y Rogers, 1969; Vandenbergh, 1989) com la que implica l’enregistrament d’un anunci publicitari, o la seva participació en d’altre tipus d’espectacle. De la mateixa manera, alguns autors han proposat quatre possibles mecanismes a tenir en compte a causa dels efectes de les primeres experiències d’aquests animals durant la seva etapa infantil i adolescent (Sackett, 1970):

- Degeneració: la privació durant la infantesa pot produir una degeneració estructural i bioquímica irreversible en els sistemes cerebrals.

- Fracàs en el desenvolupament: no pot haver-hi un correcte desenvolupament fisiològic i estructural del cervell, o aquest pot no ésser complet, si no es produeix en un ambient ric en estimulació propi o similar al de l’espècie de l’individu.

- Dèficits d’aprenentatge: La privació durant la infantesa pot dificultar l’aprenentatge de les respostes perceptives i motores per tal de fer front durant l’etapa adulta a la solució de problemes que impliquin l’adaptació de l’individu al seu entorn.

- Trauma emocional: es pot produir un estrès emocional que afavoreixi conductes com la por, angoixa, desorientació, inatenció, evitació o conducta escapatòria.

Com hem vist, aquests entorns de deprivació social en primats poden tenir efectes de per vida sobre el desenvolupament psico-socio-emocional dels individus: conductes patològiques, excessiva humanització o incapacitat per a establir vincles amb els individus de la seva espècie (Lilly, 1994), i efectes sobre la bioquímica cerebral i la funció inmunitària davant d’estímuls estressors (Coe, 1993).

Els ximpanzés utilitzats per a la publicitat són separats de les seves mares quan són cries. Aquest fet és extremadament greu ja que en llibertat aquest individus romanen amb la seva família fins a l’edat de vuit anys (Goodall, 1986). D’aquesta manera, s’està produint un mal psicològic irreparable, ja que la separació traumàtica d’un primat superior del seu grup natural, o de la seva mare, provoca estrès e inseguretat que poden ocasionar dificultats en el seu desenvolupament posterior com a adult (Abelló, 1999), o simplement com a membre de la seva espècie. D’igual manera, els entrenaments als que estan sotmesos aquests animals requereixen de subjectes obedients, amb el que en moltes ocasions es poden produir situacions d’abús físic i psicològic, ja que els mètodes d’entrenament acostumen a estar basats en la por i la domimanció.

A l’igual que els nens i nenes humans, els ximpanzés aprenen a través de l’observació dels adults e imiten el seu comportament. Ells aprenen en un context social i els individus que no tenen oportunitat de créixer en un grup normal no podran aprendre els comportaments propis de la seva espècie, amb el que probablement acabaran mostrant tota una gamma de conductes anormals. Aquest fet, podria dificultar enormement la seva capacitat de reintroducció a grups socials establerts, que al cap i a la fi és l’única alternativa de recuperació d’aquests individus.

Abelló, M. T. (1999). Coco. Revista del Parc Zoològic de Barcelona, 1, 33-35.

Brent, L., Kessel, A. L., y Barrera, H. (1997). Evaluation of introduction procedures in captive chimpanzees. Zoo Biology, 16, 335-342.

Butynski, T., y Members of the Primates Specialist Group. (2000). Pan troglodytes. En 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (www.iucnredlist.org). Recuperado el 18 de Julio de 2006.

Coe, J. C. (1993). Psychosocial factors and inmunity in nonhuman primates: A review. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 289-308.

Feliu, O., y Llorente, M. (2005). Chimpanzees and other state-owned primates in Spain: past, present and future. Folia Primatologica, 76(1), 51-52.

Fritz, J. (1986). Resocializacion of asocial chimpanzees. En K. Benirschke (Ed.), The Road to Self-Sustaining Populations (pp. 351–359). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Goodall, J. (1986). The chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns fo behavior. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Lilly, A. A. (1994). External Stressor in Captivity. En V. Landau (Ed.), ChimpanZoo: 1994 Conference (Proceedings): The Jane Goodall Institute.

Nash, L. T., Fritz, J., Alford, P. A., y Brent, L. (1999). Variables influencing the origins of diverse abnormal behaviors in a large sample of captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). American Journal of Primatology, 48, 15–29.

Reinhardt, V., y Reinhardt, A. (2000). Social enhancement for adult nonhuman primates in research laboratories: a review. Lab Animal, 29(1), 34-41.

Sackett, G. P. (1970). Isolation mechanisms, rearing condicions and theory of early experience effects in primates. En M. R. Jones (Ed.), Miami symposium on prediction of behavior: Early experience. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press.

Sackett, G. P., Novak, M. F. S. X., y Kroeker, R. (1999). Early experience effects on adaptative behavior: theory revisited. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities. Research Reviews, 5, 30-40.

Turner, C. H., Davenport, R. K., y Rogers, C. M. (1969). The effect of early deprivation on the social behavior of adolescent chimpanzees. American Journal of Psychiatry, 125, 1531-1536.

Vandenbergh, J. G. (1989). Issues related to "psychological well-being" in nonhuman primates. American Journal of Primatology, Supplement 1, 9-15.

Robert Waterston El lunes, en CosmoCaixa-Barcelona. Foto: JOSEP GARCÍA

Robert Waterston El lunes, en CosmoCaixa-Barcelona. Foto: JOSEP GARCÍA